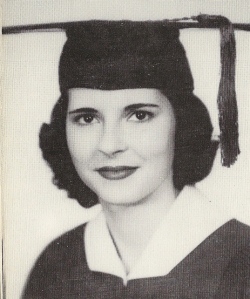

—Lisa Cade Wieland

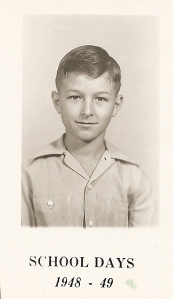

One time during one of our “semi-annual pilgrimages to the Holy Land” of my rural Arkansas birth and upbringing, I was standing on the front porch of the old Selma general store looking off toward the historic Selma Methodist Church. Behind me I heard my young son ask his mother, “Mama, what’s Daddy lookin’ at?”

“He’s not lookin’, Sean,” she said. “He’s rememberin’.”

What I was “rememberin’” as I looked up the gravel road that led toward the church and then curved to the left to continue a mile or so on to the Selma Lumber Company sawmill was a scene from my childhood.

For a certain period during the ten years that I was growing up in Selma, my mother worked in the store with her friend Minnie Mae Eason, who, with her husband, owned the store. Although my father and Bill Eason had business dealings together at times, I can’t recall whether Mama was a partner in the store with Minnie Mae or simply helped her out.

In any case, not long after Mama had begun working there, a black man came into the store one day about noon and asked Mama if he could buy something to eat and charge it. When Mama said that she didn’t know him and that he had no charge account, he explained politely that he had just started working at the sawmill that day and that he would have no money until he was paid at the end of the week.

It was common practice for the sawmill hands to walk down to the store at noon and buy individual items for their “dinner” (as lunch was called in the rural South), which they consumed out on the store porch. These items usually included a can of Vienna (universally pronounced “Vye-enna”) sausages, some soda crackers, a dime’s worth of “rat cheese” (cheddar cheese thinly sliced with precision from a huge round wheel and carefully weighed on a meat scale), an RC (short for Royal Crown Cola), and either a Moon Pie (a popular Southern confection of the time) or a “goober wheel” (a Peanut Patty).

However, since Mama was alone in the store on this occasion, she was in a quandary because she could not bring herself to sell the items to the poor hungry black man who had no credit and no proof that he was actually employed at the mill. When she told him so, he sadly turned and walked out of the store to start his long weary trek back up to the mill to put in another half-day’s work with nothing to eat or drink.

As he did so, Mama and I walked out onto the porch and watched him while he strode manfully but slowly up that gravel road, his back straight and his head high but his very demeanor giving evidence at every step of his weariness of body and soul.

As he continued his prideful but sorrowful journey, Mama stood beside me and wrung her hands as she lamented, “I feel so sorry for him. I know he’s tired and hungry. But I just couldn’t let him have those things, because I didn’t know him.” It was obvious that she was “feeling his pain,” yet was pained herself because she felt she could do nothing to relieve his misery.

That was the scene that I was remembering more than thirty years later as I stood on the front porch of the old store looking up the road toward the Selma Methodist Church. It is the same scene that I recall each time I visit that place. Though Mama and the black man and the old store are all gone, I hope that Mama and that man are now feasting together at the Lord’s table on the store porch, and that I will one day join them there. I can almost taste that RC and Moon Pie.

Mama’s Lack of Racial Bias and Social Conformity

“Just what is it we all want . . . to get back to? Myth, memory and imagination. Land, language and literature. Race and place. . . . Every generation tells the next, the South is disappearing, yet it never disappears.”

—Paul Greenberg, editorial page editor,

“Pictures at an exhibition: The South, the South, the South . . .,”

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, nd

That memory of Mama and the hungry black man reminded me of several other instances in which Mama’s perspective and treatment of black people was revealed.

Although it was “just not done” in those days in rural Southeast Arkansas, Mama gave no thought to entertaining black visitors in our living room. Obviously, in the rural South in those days these visits were few since the general unwritten societal rule was that black people would not enter the front door of a white dwelling. In fact, they would not even come to the front door and knock. Instead, they would stand outside the yard gate and call for someone to come out and speak to them.

At times some black man or another from our community would come to the gate while I was outside playing and politely ask me to call my father. I would do as I was asked, and Daddy would always go out and talk to the black man who usually stood humbly waiting, his hat held nervously in his hand. Often the reason for the visit and the requested conversation with Daddy was obvious, since Daddy would reach into his back pocket to retrieve his wallet and pull out a bill to pass to the duly grateful recipient. Somehow without being told I knew that “the word among the colored folks” was that my father was always willing to make a small loan to help the needy laborer get by until Saturday, the weekly payday.

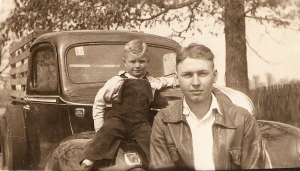

In fact, Daddy was so well known and respected in the rural black community that when he died in 1954, many of the area blacks were allowed to attend his funeral (seated in a carefully segregated section) at the all-white First Baptist Church of McGehee, Arkansas—an event that I do not recall ever happening previously.

Black women, many of whom worked as domestics for white ladies, usually came around to the rear of the house where they either knocked on the back door or just went about their assigned tasks. So for Mama to invite a black woman into the “front parlor” was quite an unusual breach of protocol, one that she never seemed to note or realize.

On one such occasion, Mama was entertaining a young black woman and her son, who was quite a bit younger than I was. For some reason, during the conversation Mama instructed me to go get my new Daisy “Red Ryder” BB rifle to show the boy and his mother.

While I was demonstrating how the rifle was cocked and fired, the little boy grabbed it with his hand around the stock—with the cocking lever down. I knew that if he pulled the trigger, the rifle would go off, and the cocking lever would fly back up and strike his knuckles sharply. So I tried to stop him by saying, “Wait, wait!” and pulling the gun out of his hands. But Mama and the boy’s mother both gave me a hard look that revealed they thought I was trying to keep him from firing the rifle—which I was, for his sake.

Sure enough, he pulled the trigger, and the cocking lever flew up and struck his clenched fingers so hard that he burst into tears. Immediately both Mama and the boy’s mother began to console the weeping boy while glaring at me in anger, obviously convinced that I had caused the boy to be hurt on purpose. I tried to tell Mama the truth, but neither she nor the boy’s mother was in any mood to listen to me. So soon afterward the visitors left, never to return.

Mama then turned, pointed her finger at me, and said, “Aren’t you ashamed?” She often did that when I had disappointed her or fallen short of her high expectations for me. Throughout my life I always knew implicitly that Mama expected me to be superior in conduct and manners—I just wasn’t supposed to act superior, even to a person I might consider inferior.

Later in life I came across a quotation that I always remembered though I never knew its source: “The mark of a great man is the way he treats lesser men.” That quotation and subsequent events in my life became the basis for one of my own quotations: “My devout Baptist mother taught me to be honest and to be a gentleman. She just never taught me how to do both at the same time.”

The result of the incident was that I was never able to vindicate myself to Mama or the woman and her son, or even to explain what had really happened and why. As in many other instances throughout my life, I was left frustrated and upset because I was perceived as the villain when I was actually in a sense the victim—of misunderstanding. I am sure that in the mind and heart of that black woman and her son I was the epitome of a cruel and selfish Southern white racist.

Mama Brought Us All to the Table

“You’ll watch Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and all the prophets march into God’s kingdom. You’ll watch outsiders stream in from east, west, north, and south and sit down at the table of God’s kingdom.”

–Luke 13:28-30 THE MESSAGE

Although there were other incidents of racial tension during my youth, the one that perhaps epitomizes most vividly Mama’s lack of racial bigotry and observance of unwritten social codes transpired after my family had left the country and moved to town in October 1948, just before I turned ten years old.

After living in several houses for several years, in 1953, when I was fifteen, we built a new ranch-style house in McGehee and began to move into it. To assist us in this move Daddy retained the services of one of his former Selma “hands,” a black man whom I will call Charlie.

In the process of moving, we had transported part of the furniture and other belongings when it came time to have “dinner.” Mama had been busy making sandwiches, chips, and iced tea (“the table wine of the South”) and had set them out on the kitchen bar. As we were passing through the kitchen she began to urge us—all of us, including Charlie—to fill our plates, sit down at the table, and eat.

Since it was unthinkable in the South during those days for blacks and whites to eat at the same table, Mama’s inclusion of Charlie in her invitation left us all confused, not knowing what to do. Charlie seemed as uncomfortable as we were. I am sure he would have been much happier to step out on the back porch and wait for a plate of food and a drink to be handed to him to consume in isolation, as was the established custom in those days. But Mama was not following the unwritten code of conduct, which caused everyone great discomfort.

Finally, after we had stood and shuffled our feet for a few minutes, Mama intervened and insisted that we fill our plates, sit down, and eat—which we did. We were all noticeably relieved when the meal was over and we could get back to our moving chores.

That was the first time I ever sat down at a table and ate with a black person. The second time came in the mid-sixties when I was accepted to attend a U.S. government-sponsored French-language institute for high school teachers, including both blacks and whites, held at what was then Kansas State Teachers College in Emporia, Kansas. Since there were forty-four participants and a dozen native-French speakers and teachers, we were broken up into groups and assigned to eat at different tables with different participants and teachers for each of the seven weeks of the institute.

I must admit that the first time I sat again at a table with a black person was a rather traumatic event in my life, though I tried not to show it. As the weeks went by and I changed from one table to another the “novelty” gradually wore off and the experience became a normal routine. As such, it was just the beginning of a long process that gradually led me to accept black people as equals—a process that Mama never had to go through because she always accepted and treated everyone as children of God and brothers and sisters in Christ.