“The daily newspaper—a record of prehistory.”

—Jimmy Peacock

“We long to be allied with two things: with all the people who came before us—tradition—and also with our hope, so we can transcend life.”

—Dale Brown, Of Fiction and Faith

In my previous post I offered Part I of the story of the murder of my grandfather Rev. Willis Barrett’s first wife Edna Ella Fox Barrett while she was carrying their first child. That story was taken verbatim from a newspaper article in the Dumas (Arkansas) Clarion of Wednesday, December 31, 1980.

The actual story, which took place in my birthplace of Selma, Arkansas, was dictated by my grandfather to my mother who recorded it word for word in a Big Chief tablet. (To read this story, go to my previous post titled “Memory of a Selma Family Tragedy.”)

In this second post about the same subject, I offer Part II of that story, which was written by Mrs. Marion Stroud of our hometown of McGehee, Arkansas.

Mrs. Stroud was the wife of Hilliard Stroud, one of the officers of the McGehee Bank who was a friend of my father Arthur Peacock, especially after my family moved from Selma to McGehee in 1948 when I was ten years old. She was also actively engaged in the Desha County Historical Society for many years.

A year after our move to McGehee, I became better acquainted with Mrs. Stroud when she was my sixth-grade teacher in the McGehee Elementary School, a class that was held in one of the converted barracks from the WWII Japanese-American Relocation Camp at Rohwer, about twelve miles northeast of McGehee. (For more about these buildings and the camp, read my earlier post titled “Opening of WWII Japanese American Internment Camps Museum” published on March 20, 2013.)

I had known the Strouds for decades before I learned that they had a direct connection to the triple murders described in Part I of these stories. It seems that the older couple, the Stephensons, who were murdered along with Edna Ella Fox Barrett, were relatives of Mr. Stroud. Before that time I had no idea that the Strouds had any connection to my birthplace of Selma, much less that their family was part of the tragedy that took place there in December 1904.

Here now, exactly as it was presented in the Dumas Clarion on Wednesday, January 7, 1981, is the account of the murders from the viewpoint of the Strouds whose relatives also lost their lives in that tragic event.

The opening and closing editor’s notes were part of the original Clarion article, which had no photos or captions. As with the first part of the story, I have made some minor editorial changes and insertions set in brackets, capitalized and lower-cased some words for consistency of style, and divided some longer paragraphs into shorter ones.

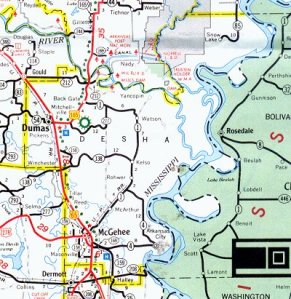

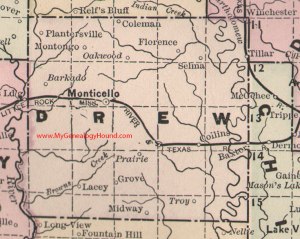

Below I have inserted maps of Desha and Drew counties in Southeast Arkansas with some of the places mentioned in the following text.

Map of Desha County, Arkansas, with portions of Drew County, Arkansas, and Bolivar County, Mississippi. McGehee is near the bottom of the map with Tillar and Winchester a few miles northwest on U.S. Highway 65 along the Desha-Drew county lines. Dumas is north of Tillar and Winchester, while Selma is west of Tillar. Northeast of McGehee is McArthur and beyond it Rohwer, the location of the WWII Japanese American Relocation Camp. The Mississippi River is to the east (right) of McGehee with Bolivar County, MS, across the River. Gaines Landing is a former port on the River below Arkansas City, the seat of Desha County. (To magnify, click on the map.)

Drew County, Arkansas, with Selma in the upper right; Tillar, Winchester, and McGehee (in Desha County) to the extreme right of Selma; and Monticello, to the southwest of Selma. Fountain Hill (in Ashley County) lies south of Monticello. (To magnify, click on the map.)

Part II

“Selma tragedy: triple murder”

(Editor’s note: This is a second part of the story of a triple-murder at Selma in 190[4], which was discussed at the Desha County Historical Society meeting in McGehee recently.)

By Marion Stroud

Late in December 190[4], William (Billy) Stephenson, his wife Jennie, and Edna Barrett, who was pregnant, were murdered at the Stephenson home on the old road between Selma and Monticello. The house was burned.

Despite reward offers and investigations and hunches and rumors, the triple murder was never solved although the motive seems clear enough. Just that day Stephenson, who did not trust banks, had been to Tillar [east of Selma and north of McGehee] to sell his cotton and it was believed he had the money home with him.

There had been a dance that night at Selma, which back then was nicknamed Shanghai, and Edna Barrett was staying at the Stephensons’ because Billy Stephenson had asked her husband [my grandfather Willis Barrett] to take his fifteen-year-old daughter, Alberta, and her half-brother Frank Hayes to the party.

[As described in my grandfather’s account of the events of that evening, he returned from the dance to the Stephensons’ house only to find his wife Edna and the Stephensons brutally murdered and the house burned down with their dead bodies inside.]

Even in those days when roads were bad and communication was difficult word of the crime spread quickly and the people of Drew and Desha counties reacted with shock and horror. The murderers, many believed, had to be neighbors, people who knew about the dance at Selma and knew that Billy Stephenson had his cotton money with him.

Even today, old timers have their theories about who murdered the Stephensons and Edna Barrett. Even today they will whisper the names of the persons they suspect of the crime. Still no one knows for sure who the murderers were or how they escaped detection in such a small, isolated community.

Something is known, however, about the victims.

William Stephenson was the son of William and Malinda Stephenson of Bolivar County, Mississippi. His father died of pneumonia either just before or just after William was born. In 1860, he was living in Bolivar County with his mother and his step-father, Joseph B. Stroud, his three sisters, Josephine, Ellen, and Victoria, and half-brothers, Calvin, age 2, and George Washington Stroud, 6 months.

The childhood of the young boys was spent in a [Mississippi] river town constantly being shelled by Union gunboats and raided by the soldiers—education was non-existent, the economy in chaos.

In 1867 [two years after the end of the Civil War], thirty-four-year-old Joseph Stroud died, leaving his wife who was now forty-two. The older girls were married, but Malinda had the three little boys and a little girl Jennie Matilda Stroud to care for, and these were the worst of Reconstruction Days.

The daughter Ellen had married a Mr. O’Banion who was a Civil War soldier. He was wounded and died on his way home. Ellen later married a Confederate veteran J.T. Lilly who owned a ferry at Old Eunice on the [Mississippi] river in Chicot County [Arkansas]. Mr. Lilly brought his mother-in-law up Bayou Macon during flood time and settled the family on what is now the J.H. Stroud farm. The widow evidently bought the place, for back taxes by her son Calvin. Malinda was living here when the 1870 census was taken.

The nearest post office was Gaines Landing. Then Malinda Stroud was head of the household and living with her were Willie, age 13; Calvin, age 11; George W., age 10; Jennie Matilda, 8; and an orphan child, 2.

At that time the farm was in Chicot County, but in 1879 when it was sold, the land was in Desha County. In 1872, Malinda Stephenson died. She is buried in the McArthur (Arkansas) Cemetery at the top of a small mound. Her little boys planted a wild cherry tree at the head of her grave.

By 1880, William Stephenson had married Nancy Duff, and they had a one-year-old daughter Kate. The family lived in Richland Township, Desha County.

In 1887, Mr. Stephenson, then living in Drew County near Selma, married Mrs. Jennie Hayes of Prairie Township, Drew County. She had one son, Frank Hayes.

In 1896, Stephenson had Z.T. Wood, a Monticello lawyer and grandfather of Judge Warren E. Wood of Little Rock, draw up his will. R.W. Harrell of Selma (later of Tillar) was named executor. Witness[es] were J.T. Wood, R.L. Hyatt, and J.L. Prewitt. Wood and Hyatt in 1904 signed a statement saying that the 1896 will was Stephenson’s last will and was witnessed by them. Proof of the will was filed for probate [on] December 31, 1905, by J.W. Kimbro, Drew County Clerk.

The will was unusual in that it provided for the wife Jennie in her widowhood so long as she did not let her son Frank live with her or on the money Stephenson left Jennie. His daughter Kate, who was not living with them at the time, receive[d] $5, but his only other child Alberta would receive “the remaining portion of my estate real, personal and mixed of every sort or character.”

Gertrude Stroud Boyd, daughter of George W. Stroud, remembers the night when a group of men on horseback awoke her father’s household at their farm on Bayou Macon with the terrible news of the tragedy at Selma and of the death of her father’s half-brother, William Stephenson. George Stroud immediately dressed and rode off to Selma. He later hired a private detective to track down the criminals, but nothing was ever proved.

People over the two counties [Desha and Drew] were shocked, and it was the general opinion that the triple crime of murder, robbery and arson was the work of local people whose motive was robbery, that the victims were first killed, then robbed, and the house was burned to cover up the crime. A known group of horse and cattle thieves operated in the area all the time. They rode and stole at night and led respectable lives by day. Again, no proof.

A new family, very poor, lived in a shack away from town, having little to do with Selma people. A son of this family disappeared but came back to his family sick with smallpox. The entire family died of the disease, and the same righteous settlers thought the boy had committed the murder, and the Lord [had] punished the entire family. Someone else said the criminal is buried in Mount Tabor cemetery [near Selma] with a nice stone at the head of the grave. People checked to see if the suspect had been at the dance and [had] slipped away to do the mischief. Even today an old timer whispered the name of a man of good family that he knew was guilty. But as far as anyone knows there was never even an indictment.

The probate of the case was closed in 1907. In 1911 Alberta Stephenson Wood and her husband, Ashley B. Wood of Ashley County, sold 320 acres of land for $1500. It was Alberta’s land, as the deed stated.

What of Kate, the older daughter mentioned in the will and left $5[?] Relatives in Desha County remember her as Cousin Kate, but nothing else is known.

Frank Hayes, the step-son who attended the dance with his half-sister, Alberta, and Willis Barrett, and who was left out of the will—what became of him[?] And nobody seems to know. But relatives in Desha County, who as children visited in the Stephenson home, remembered that they rather liked Frank and thought Uncle Billy was a bit hard on the boy.

This is the story of what happened near Selma in December, 190[4]—murder, robbery and arson, and of the people involved, a happy young expectant mother who looked forward to celebrating her first wedding anniversary, a hard-working farmer who didn’t trust banks, and his fifty-four-year-old wife, Jennie Hayes Stephenson.

Note: Since this paper was read to the Desha County Historical Society, the author has learned that at age sixteen, Alberta married Mr. Wood, a druggist at Fountain Hill [in Ashley County]. They had four children. Alberta developed tuberculosis, and Mr. Wood sold his drug store and other property and the family moved west for his wife’s health. There she soon died. It may be that she sold her property near Selma (1911) just before they moved.

[Blogger’s note: When I was a child and the story of this triple murder was still rather recent news, a rumor went around Selma and the surrounding area that an elderly lady had taken sick and thought she was going to die. So in fear of facing her Maker with a guilty conscience she confessed that it was her three sons who committed the horrendous crime.

[She said that they wore masks and had only intended to rob Mr. Stephenson of his cotton money. However, she claimed that one of the three victims recognized the intruders, called them by name, and pulled down their masks. At this disclosure and reacting out of fear and panic, the three thieves murdered the victims by the use of axes, chopping off Mr. Stephenson’s head and striking Edna Barrett a fatal blow to the chest. They then set the house on fire in an attempt to hide the evidence of their crime and made it impossible to be identified by it.

[However, as the rumor went, the elderly lady in fact did not die as expected, so she quickly changed her story, denying it entirely, claiming that she was out of her head with fever and delirium. The result was that no conviction of her sons was ever made. However, those who knew her and them always believed that she told the truth, even though she recanted when she regained her health.

[The end result was that no one was ever indicted for the crime, which is still unsolved to this day.]

Sources

The map of Desha County, Arkansas, was taken from the following source and may ordered from it:

https://myokexilelit.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/deshacounty.jpg

The map of Drew County, Arkansas, was taken from the following source and may be ordered from it:

http://www.mygenealogyhound.com/maps/arkansas-maps/ar-drew-county-arkansas-1889-map.html