“When I first went north, I was surprised to learn that there were people in the world who did not know that Arkansas has both a delta and a culture that goes with southern lowlands.”

—Margaret Jones Bolsterli,

a native of Desha County near McGehee,

writing in Born in the Delta

“They [an outside film crew] asked me what it was like to come from a place [the Arkansas Delta] where your family has been for generations—it was impossible to put into words.”

—Vivienne Gould Schiffer, author of the book Camp Nine,

in personal email to Jimmy Peacock

In my last post I wrote about the opening of the WWII Japanese American Internment Museum in my hometown of McGehee, Arkansas. To learn more about that museum and the internment camps near McGehee that it chronicles, please refer to that post.

In that post I inserted a link to a book of historical fiction titled Camp Nine about the camp nearest McGehee. To learn more about the book, click here. To purchase a copy of it, click here.

That fictional work was written by Vivienne Gould Schiffer, the daughter of former McGehee mayor Rosalie Santine Gould who was instrumental in collecting, preserving, and displaying many of the artifacts from the camps.

In this post I would like to present a review of that book; however, not in the usual sense of that term. [To read two excellent reviews of the book describing its content, characters, and storyline, visit the Amazon.com Web sites listed above and then scroll down.]

Important Themes in Camp Nine

“Thank you for your remark about Gerald [O’Hara] who ‘recognizes that security can never be found apart from the land.’ No one else picked that up; no one seemed to think about it or notice it. And that depressed me . . . . And I felt . . . that I had utterly failed in getting my ideas over.”

—Margaret Mitchell in a letter to Gilbert Govan in 1936,

from The Irish Roots of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind

by David O’Connell

In this review rather than focusing on the story or the camp itself I hope rather to offer a glimpse into the fascinating and often incomprehensible locale in which the story takes place: the Arkansas Delta of the 1940s.

This is made easier by the fact that the story in narrated by a little girl named Chess who describes her own experience with the camp and its inhabitants—and the surprising effect it has upon her and her family—especially her view of herself and her sheltered world, as well as her limited and often false perspective of others who are different from her.

As I have noted in a personal email to the author, who gave me full permission and approval to quote these passages, the book is reminiscent of several other notable works about the South in general and the Delta in particular.

For example, Born in the Delta by Margaret Jones Bolsterli (from Watson, Arkansas, near the camp); A Painted House by John Grisham (who was born in 1955 in the same hospital in Jonesboro, Arkansas, as our younger son Keiron in 1970); To Kill a Mockingbird (especially the character of the narrator, a little girl called Scout); the book and film titled The Help (about the relationships between Southern black maids and their white mistresses in the 1960s); both the play and the movie made of Tennessee Williams’ classic Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (set in the Mississippi Delta just across the River from McGehee); Crossroads (a 1986 film about an old black Delta man who tries to teach Blues music to a young white boy from New York); and especially Gone with the Wind (the classic 1939 Southern book and film that reflects so many of the themes in Camp Nine such as the importance of land and a sense of place).

It also shares some themes with my own coming-of-age story in the Arkansas Delta titled “Yo Recuerdo” (“I Remember”) and other posts of Delta quotes (mine and others’) on my blog (see the list at the end of the post).

In fact, I was so impressed by Camp Nine that I tabbed about twenty-five quotes and excerpts in it, almost all of them about the Arkansas Delta and particular aspects of it such as: the presence and influence of the Mississippi River and its vast levee system and verdant lowlands; Southerners’ attachment to the land; the importance to Southerners (especially Deltans) of a sense of place; the power of memory and the past; the nature and role of Blues music; the cultural dominance of racial bias and unwritten societal taboos, etc.

Many of these same themes were also addressed in the other books, plays, and films noted above, and especially in my own Delta writings.

Quotes and Excerpts from Camp Nine

About the Arkansas Delta

“To understand the story, one must understand the place, for the events could not have transpired anywhere else.” (p. 7)

“It was such a romantic notion that it bore no resemblance to the dangerous, depressed region that I knew so well. But Henry countered that no one could really appreciate one’s home except through the eyes of outsiders, and I’ve since come to accept that he was right.” (p. 67)

Following are some select quotes and excerpts from Camp Nine that relate to the Arkansas Delta. I have divided these quotes and excerpts into groups under subheadings loosely based on some of the same attributes of the Delta discussed in other sources and in my own blog posts on various aspects of the Delta (see the list at the end of this post). I have set these quotes and excerpts in quotation marks with my inserted comments in brackets, and my emphases in italics.

The Mississippi River, Levee System, and Lowlands

“Past the tenant shacks, the levee rose like an emerald mountain, and the Mississippi River, invisible on the other side, was even larger in my imagination. At the time, I didn’t appreciate how deeply the levee [and the river the levee was built to restrain] influenced our lives. Massive and splendid, it seemed to be alive, a colossal creature coiled beside us.” (p. 32)

“The Lincoln lurched suddenly down a small path, straight down the side of the levee. My stomach fell out from under me, and I gripped the door of the car until we came to a stop at the remnants of a . . . village. In front of me, stretching away from the levee, a quiet slough wound among banks of cypress trees hooded with Spanish moss.” (p. 155)

“Like the others, Willie’s shotgun house was arranged with one room after another, straight from the front door to the back. An African design that encouraged airflow through the structure, a shotgun house was so named because legend had it that a person could stand in the front door and shoot a shotgun, and the buckshot would go straight out the back door.” (p. 62)

“Crooked and wild, the bayou cut a narrow swath across the county on its way to the [Mississippi] river. Its impenetrable, chocolate-brown waters were home to countless turtles, lizards, and fish, including the fierce-looking remnant from prehistoric days, the alligator gar, with its bulging eyes and razor-sharp teeth. [Today after decades of being hunted to virtual extinction, the bayou would also be inhabited by genuine alligators.] Dotted along the bayou’s length was an occasional deep eddy, suitable for swimming only to the brave few. . . .

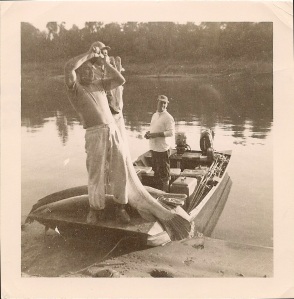

Alligator gar with the author’s father Joe Gould Jr. hidden behind the gar (photo courtesy of Vivienne Schiffer; to magnify, click on the photo)

“Nestled in a caved-in crook of the bayou was a deep pocket that had been carved from the bank by the swiftly moving current. The roots of giant cypress and oaks formed a living lattice as they reached from the bank to the base of the stream. The murky water inside the graceful, natural cage roiled with life. It was a water-moccasin [deadly poisonous snake] den to end all others.” (p. 60)

“I maintained that it seemed that Mark Twain couldn’t have been talking about the same Delta that I knew, although he spoke with real affection for the long gone city of Napoleon [Arkansas], once located on the banks of the Mississippi River merely a mile or so from the Morton Plantation. A large river port, it had been an important stop during Civil War times, and ambitions for the town had loomed large. But the river had its own ideas, and Napoleon had slid from its banks and vanished beneath the waves shortly after, leaving nothing but occasional artifacts buried under towering vines.” (p. 67)

Delta Blues Music

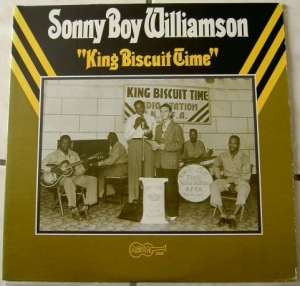

Sonny Boy Williamson who played Blues music on the King Biscuit Time Blues show on KFFA in Helena, Arkansas, at the time of Camp Nine (to magnify, click on the photo)

“‘This here what they call the blues, Little Miss. You get the blues when life get you down, and you can’t do nothing but sing it out loud. Back in the levee camp, you ain’t got nobody. You all by your lonesome self. Colored folks can’t tell nobody the truth ’bout the things that happen to them. So they bury it in song. Blues song don’t never mean what it say. You got to listen past the words to find the truth. . . .

“‘That boy, David, he know the blues. Say it speak to him like no other. He lonely, too. Away from home. Got no one to show him the way.’” (p. 87)

“Willie stopped him. ‘That’s alright, boy, but you ain’t feeling it. It ain’t ‘bout many notes you can juke out that box [guitar]. You got to feel the blues. Try it again.’” (p. 107)

Segregation and Southern Social Customs

“‘The Delta [itself] is a prison.’” [Response to statement that the Japanese-American internment camp in the Delta was a prison.] ( p. 49)

“The convention of our day and region dictated that we live in a social contradiction of familiarity and distance. She [Ruby Jean, the black maid and cook] could never come right out and say what she really meant about any of us [the white family for whom she worked]. The rigidity of societal norms was as much a part of the landscape as the river itself.” (pp. 30-31)

“It was possible for the white people of Rook to interact with black people, and for the white people of Rook to interact with the Japanese [from the internment camp]. In each case, it was acceptable only if initiated by a white person. But contact between the blacks and the Japanese? How could I explain to David that it simply wasn’t done? I didn’t even understand it myself.” (p. 69)

“A white child could not have walked alone through the black community. Every town in the Delta, even a tiny burg like Rook, had both white and black sections, with the black inhabitants vastly outnumbering the white ones. Larger, louder, and more colorful, the black sections were separated by a thick rope of custom.

“But there were written rules as well. I recall once, on a trip to Pine Bluff as a small girl, having to go to the bathroom, badly, and being in such a clamor when we finally stopped at the filling station that I raced to the first door I saw. When I emerged, Mother waited placidly, but a small, disgruntled crowd of [white] men had appeared, watching me as the door opened. Above the door was a sign: ‘colored.’ I had breached the decorum. I can only imagine what would have happened if the circumstances had been reversed, if I had been a hurried black girl in search of a bathroom and had rushed into the door marked ‘white.’” (pp. 82-83)

“‘No, ma’am,’ I said [to Ruby Jean], breaching another convention. To my grandparents’ dismay, I addressed all adults as ‘ma’am’ or ‘sir,’ regardless of their race. Grandma had scolded Mother about my lapses of correctness on numerous occasions, and had tweaked me directly. In her view, black men and women did not deserve such respectful terms from white people. But Mother responded to her by smiling and saying I was such a polite child, I couldn’t help it.” (pp. 93-94)

“But it told me something about all of us, that we categorize each other according to our similarities and differences. Willie [an old blind black man] couldn’t see David [a Japanese-American boy]. But he could hear him [speak]. And his ears told him that David wasn’t from around here.” (p. 85)

“‘See?’ [said David to Chess. ‘You have] lived your whole life in the Arkansas Delta, and you can’t name me one [black] bluesman. And you know why? Because you’re a cultured, white woman. But I’m not white, Chess. I always thought I was, growing up [in California as a Japanese-American]. But I really didn’t know what white was until the United States government carved us out of the white race, set us on a plate, and served us up into a dark corner of Arkansas. That’s when I learned what white really is. It’s separate. It’s sheltered. It’s a race apart.’” (p. 193)

A Delta Belle holding a magnolia blossom and standing in front of an antebellum home (to magnify, click on the photo)

The Land, Sense of Place, and Delta “Victims”

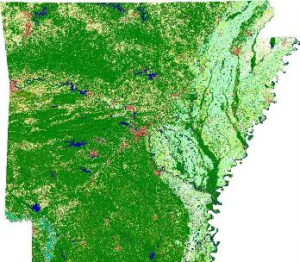

The Arkansas Delta (the light-green area on the right side of the photo along the Mississippi River; to magnify, click on the photo)

“In the plantation world in which we lived, land was power. Those with it controlled those without it, pure and simple.” (p. 11)

“Mr. Hayashida [one of the Japanese-Americans from the internment camp] kicked a clod of buckshot [local term for the Delta soil] with the toe of his rubber boot. ‘Oh,’ he murmured, ‘this is good earth. Very good earth.’ He picked up a handful and broke it between his fingers. It fell to the ground in tiny balls like BB gun pellets [the source of the term “buckshot”]. ‘You just got to work with it [word italicized in original copy]. You can’t make it into something it’s not. Kind of like people, right? . . .

“‘The land here is very unusual,’ he said, stopping where the brown earth ended and colored [plowed] rows began. ‘Doesn’t like to retain the water. Wants to always send the water somewhere else, so you get flooding all the time. I think I understand it though.’ He surveyed the bright distance toward the levee as the cicadas tuned up in the low branches of the trees that surrounded us. ‘That river over there is the mightiest river in the world. It wouldn’t do for there to be just any dirt around here. The dirt must have its own strong personality. It won’t back down to the river. It won’t back down to men. You have to understand it and work with it. Not against it.’” (p. 121)

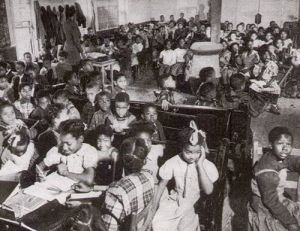

Large-scale farming of the Arkansas Delta in the decade before the opening of Camp Nine (to magnify, click on the photo)

“‘Camp Nine,’ he [Chess’s grandfather] said. ‘That was your land. I know you know it ’cause your mama chewed my ass about it for a whole year. . . . Fifty years ago, this land wasn’t anything but canebrakes and bottomland. Now there’s opportunity as far as the eye can see. If you stop to think about what’s fair, the Delta will pass you flat by, girl. Do you hear me?’” (p. 164)

“As much as I had dreaded this encounter, my grandfather was offering me something no one else ever had: a sense of my place in the mystery of the Delta.” (p. 157)

“‘You can’t turn your back on everything and run away because you think you’re in love. Just when you find it,’ [Chess’s mother] said, ‘it slips right through your hands! And God help you, you better have something else in your life to take its place.’” (p. 177)

“‘There was no one else to take over the place.’ It’s the truth, but as I say it, I realize I’d never considered any other choice. I should have wanted to leave, I should have wanted to sell the land and live a sophisticated, exciting life in a distant city, but the Delta is in my blood. No other place could ever be home.” (p. 191)

“‘Are you serious? Can you really not comprehend all this?’ I’m stunned by what seems to be real fury on his part. ‘Chess, this is the Delta. This is a crazy, dangerous place. The things that happen here shouldn’t happen to people. Anywhere. And your family . . . were at the center of it. You were just a sheltered little girl. How could you have handled that kind of responsibility?’

“I’m no longer that little girl, but I suddenly feel foolish to even have been who I was. He is right. How could I have comprehended the pain that was, and still is, a daily part of life here”? (p. 195)

“I know that Camp Nine was something that should never have been. It destroyed lives and separated families; it interrupted joys and brought, in their stead, wretched sorrows. But the experience was mine, too. On a deeper level than I had ever understood, Camp Nine [like the Delta itself] had defined my life [and the lives of all who have ever lived there]. The misery of thousands had shone a light on who I was, on who we all were, here in the Delta. Would I have ever known these things without their sacrifice?” (p. 196)

Links to Some of My Blog Posts about the Delta

“Wish I Was in the Land of Cotton I” (with quotes about the Delta)

“Wish I Was in the Land of Cotton II” (with quotes about the Delta)

“Additional Quotes about the Delta”

“My ‘Bucket-List Trip’ II: The Arkansas Delta”

“Return to the Arkansas Delta: A Review”

“Days Gone By: A Delta Passing”

“Bayou Bartholomew: Two Book Reviews” (To view an hour-long video about Bayou Bartholomew with views of real alligators, alligator gar, Spanish moss, cotton fields, bayou baptisms, bayou steamboats, plantation homes, and examples of Blues music, Southern Gospel music, etc., click here and then scroll down and click onto the start arrow in the black box in the post.)

“Some Southern Stuff V: Sense of Place”

“Some Southern Stuff VI: Love of the Land”

“During Wind and Rain: Another Delta Book Review”

Links to News Reports of the Opening of

the WWII Japanese American Internment Museum

To read an Arkansas State University report with a photo of George Takei giving his address at the opening of the WWII Japanese American Internment Museum which took place April 16, click here.

To view a brief video of an Arkansas television station news report on the opening of the museum with Takei’s comments, click here.

Source of Photos

All of the photos in this post were personal snapshots except the alligator gar photo provided by the author of Camp Nine and the following:

1. The photo of the Mississippi River was taken from The Mississippi River by Ann McCarthy (Crescent Books, New York, 1984).

2. The photo of Blues musician Sonny Boy Williamson was taken from: http://eboutique.ric-vintage-records-shop.com/WebRoot/Orange/Shops/d3d8e5da-2056-11de-a9cd-000d609a287c/4ADC/E9F9/1F20/327F/258E/0A0A/33E9/B816/33-SonnyBoyW-KingBiscuitTime-1.JPG

3. The photo of the Delta segregated school was taken from: http://www.blackpast.org/?q=perspectives/remembering-brown-silence-loss-rage-and-hope

4. The photo of the Delta Belle was taken from: a travel brochure published by the Helena Advertising and Tourist Promotion Commission, 622 Pecan, P.O. 495, Helena, Arkansas 72342; (501) 338-6583.

5. The map of the Delta was taken from an online source.

6. The photo of large-scale farming in the Arkansas Delta was taken from a post card published by the Delta Cultural Center, 95 Missouri Street, Helena, Arkansas 72342; (501) 338-8919.